On January 30th, from 12pm EST to 10pm EST, an impressive roster of historical fiction authors and bloggers are hosting a Facebook party in honor of historical fiction, the 2,023rd anniversary of the Ara Pacis, and the release of Stephanie Dray's newest book, Daughters of the Nile: A novel of Cleopatra's Daughter.

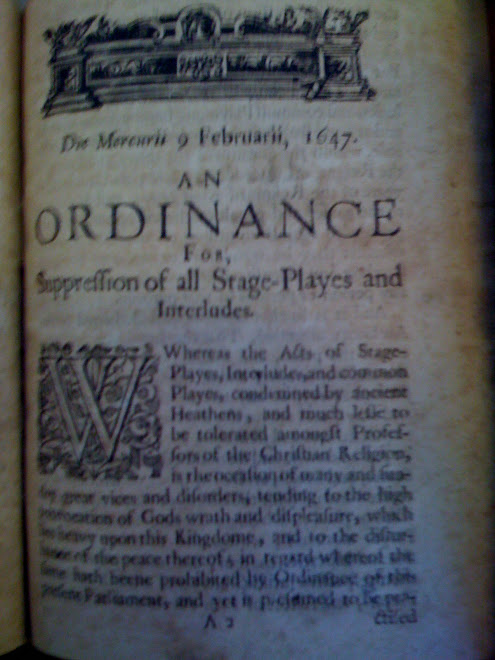

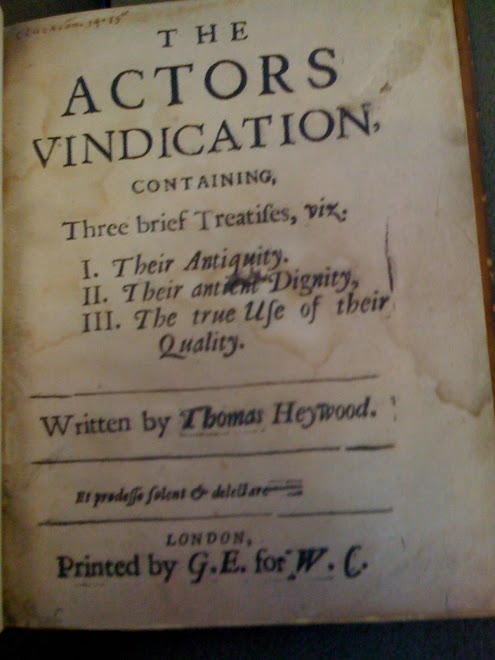

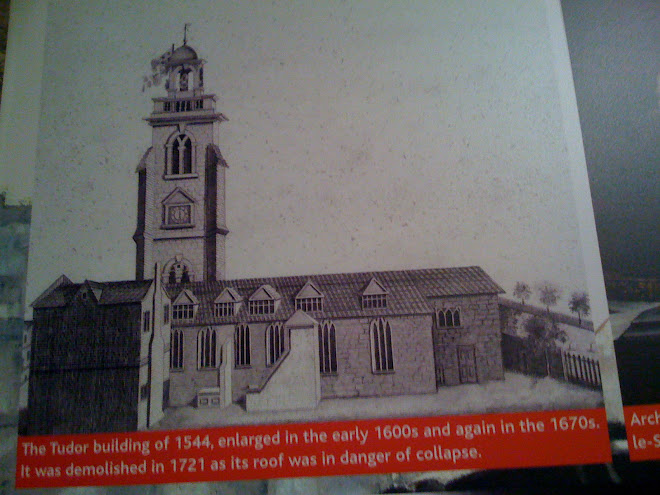

When Charles II was restored to the throne in 1660, he very soon authorized the reopening of the theatres, which had been closed since 1642 under Oliver “Killjoy” Cromwell. Since there were no new plays, the acting companies first turned to works that had been popular in the past. The King’s Company and the Duke’s Company divided Shakespeare’s plays between them. Among those assigned to the King’s Company were Coriolanus, Titus Andronicus, Julius Caesar, and Antony and Cleopatra, all of which were set in ancient Rome.

Shakespeare’s plays were some of among the first to be presented, but once the playwrights got busy, turning out an enormous volume of new plays, there was less call for Shakespeare. But the histories, and especially the Roman plays, were popular, partly because they could be used as political propaganda. Coriolanus, for example, with its struggle between those born to govern and those elected to govern, would have had a lot of resonance for English audiences whose lives had been very much affected by the overthrow and execution of King Charles I, the installation of Cromwell as Lord Protector, and finally the restoration of the monarchy—the Restoration, which gave the era and its name.

Shakespeare’s plays were often performed in adapted versions, which frequently contained political overtones. Nahum Tate’s adaptation of Coriolanus, The Ingratitude of a Commonwealth, used about sixty percent of the lines from Shakespeare’s play, though many of them were revised. It appeared in the wake of the Popish Plot, as Parliament was debating the Exclusion bills, which would bar the succession of the exiled Catholic Duke of York (later James II).

Edward Ravenscroft’s adaptation of Titus Andronicus has a preface stating that “it first appear’d upon the Stage at the beginning of the “pretended Popish Plot,” a period of anti-Catholic hysteria in the autumn of 1678. Its prologue and epilogue have been lost, but those customized bits appended to the beginning and ends of plays were frequently very topical. Julius Caesar, with tyranny and rebellion at its heart, could be made to have contemporary parallels, as it still can and is.

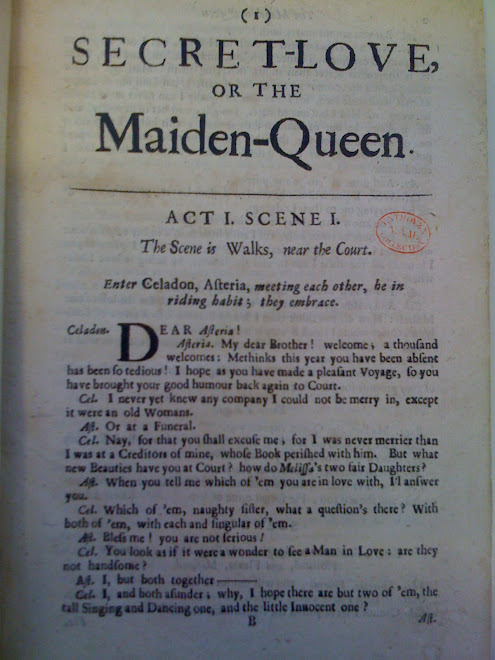

One of the most popular revisions of Shakespeare’s Roman plays was All for Love, or the World Well Lost, an adaptation of Antony and Cleopatra by John Dryden, who had been made Poet Laureate in 1668. Presented in 1678, the play’s action takes place over a few days and entirely in Alexandria, unlike the original, which spans years and continents.

On February 12, 1677, the Duke’s Company presented Sir Charles Sedley’s new version of Antony and Cleopatra, with a musical setting by Jeremiah Clarke, , with the stellar actor manager Thomas Betterton in the role of Antony and Mary Lee as Cleopatra. The show played on the next two days, too, indicating that it was a hit.

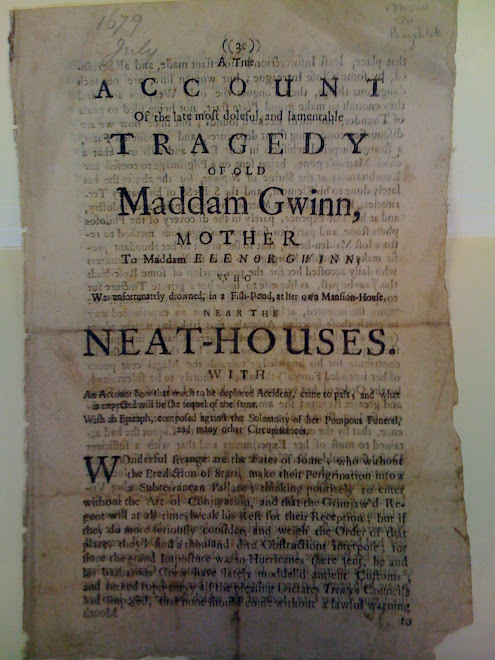

Restoration playwrights wrote original works set in Rome, as well. Dryden’s tragedy Tyrannick Love, or The Royal Martyr tells the story of St. Catherine, who was murdered by the Roman emperor Maximus because she wouldn’t submit to his sexual advances. Nell Gwynn played Valeria, the daughter of the tyrant emperor. She stabbed herself and died at the end, but the tragic mood didn’t last. When two solemn Romans came to carry off her body, she jumped to her feet and cried, “Hold, are you mad? you damned confounded dog, I am to rise, and speak the Epilogue!” And then she did, declaring:

I come, kind Gentlemen, strange news to tell ye;

I am the Ghost of poor departed Nelly.

Sweet Ladies, be not frighted; I’le be civil;

I’m what I was, a little harmless Devil.

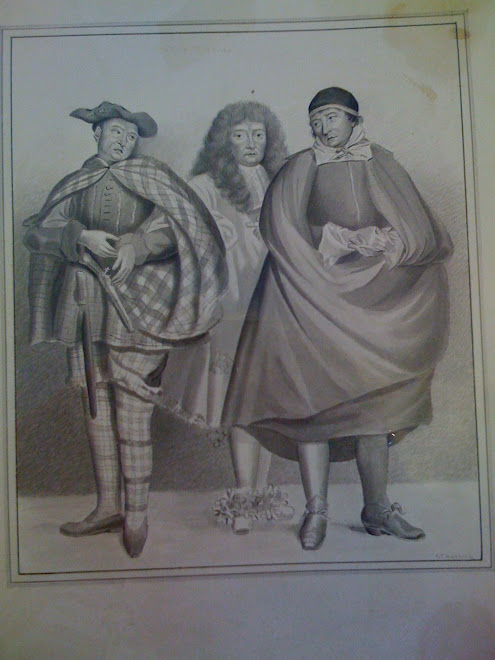

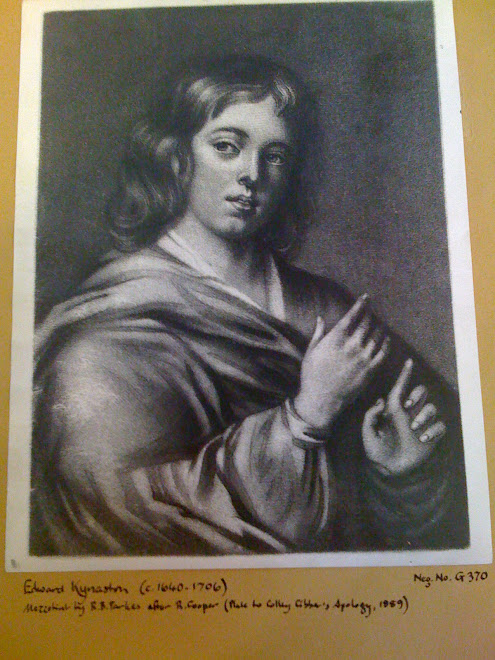

The Romans in Shakespeare’s plays are essentially Elizabethan Englishmen, and he made no attempt to keep out anachronisms. [clock] If there were attempts to suggest period dress in the costumes, they weren’t accurate, and the same was true in the seventeenth century. Just as we can usually identify pretty well in what era a historical movie was made because the style of the modern period overlays the historical dress, the clothes of the Restoration “Romans” were more like what the audience was wearing than what would have been seen in ancient Rome.

Classical subjects were also used for court masques, and there the costumes were wildly extravagant and highly fanciful. Calisto, presented in 1675, featured Roman combatants in silken armor of gold and silver decorated with gold fringe, “gold purle rosets,” jewels, spangles, and feathers. The costumes for the one-time performance cost more than £5000, at a time when shopkeepers and tradesmen earned about £10 a year, and more than enough to pay off the entire company of a ship that had been at sea for a couple of years, when sailors were perpetually begging for past-due payment.

A sketch for a “Roman habit” based on a contemporary records shows a gentleman in heeled shoes, cuffed gauntlets, long hair, and a skirted coat very much in the Restoration style. A sketch for Diana shows the goddess of the hunt pulling her bow, but she would have had a hard time running in her stays, enormous hooped skirt, and three-foot feathered headdress.